“Homie the Clown” is one of the funniest things ever written by a human. That human is John Swartzwelder. If you’re reading this you already know who he is, you already know why he’s great, and you should definitely read The Time Machine Did It if you haven’t done so yet. The thing about “Homie the Clown” is, as a season six episode, it’s far removed from the vérité mandate of the Brooks chaperoned early years (Homer’s already gone to space by this point) and it offers the viewer a ridiculous farcical narrative. The concept is high: “What if Homer was Krusty?” The plot is thin, the characters are themselves as liquid concentrate, and the ending is essentially a fake-out that renders the whole thing meaningless. Yet the episode not only works, it excels. So why is this amazing, and say “Saddlesore Galactica” not? My money’s on the tenor.

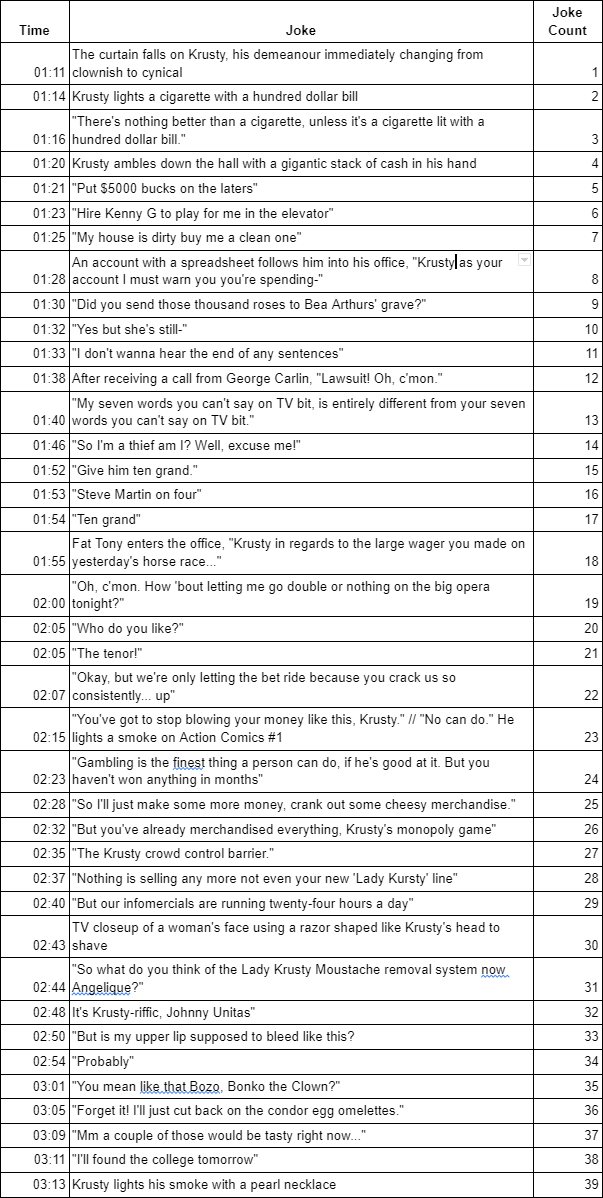

“Homie the Clown” is best understood by the bravura performance of its first five minutes, possibly the funniest five minutes in Simpsons history. The episode starts with an extremely truncated opening sequence: chalkboard gag, Homer screams in front of the garage, couch gag. It’s over in less than thirty seconds. Then comes forty-one seconds of crucial setup, Bart and Lisa watching Krusty perform a trick with a miniature trike and a loop-de-loop on his eponymous show. Shortly after this, all hell breaks loose. Here’s how the next 2 minutes unfold joke by joke.

I’ll get the obligatory out of the way first.

In the space of just over two minutes, we get thirty-nine jokes. It’s often said that in “Last Exit to Springfield” the jokes come in about every five or six seconds. In these two minutes of “Homie the Clown” it’s every three seconds. It’s not just that the jokes are there but every one of them lands. There’s obviously a subjective quality in assessing what is or is not funny, and the level of mirth extracted by each of these of course exists on a spectrum, but on a technical level a setup and a payoff have been achieved for each one, and exactly one complete joke has been written each time. It doesn’t really feel that way because they just fly in left & right creating this tsunami of specific information, like listening to Ka or reading Pynchon. The way this is achieved is through multiple layers of setup and payoff, a killer stack of jokes piled upon jokes, where each one supports the next.

The first two sight gags establish two things: Krusty is dead inside and slave to his vices (Joke 1) and that one of those vices is that Krusty pisses away his money (Joke 2). Every joke in this sequence springs from these two gags as setup. I could go through each joke one by one and tell you how the knee bone’s connected to the leg bone, but it’s information that’s best expressed visually.

From the initial sight gag three punchlines are landed, and from the second twelve punchlines are landed. Joke 8 and the introduction of the accountant lead to a further fifteen jokes across two branching paths. Beyond that twenty punchlines total serve as setup to further jokes. It’s a nuclear chain reaction of comedy, and far funnier than the Oppenheimer movie, I presume. Note that in purple he also manages to thread a ‘rule of three’ thing in there at roughly the start, midpoint and end of the sequence, with what outrageous item Krusty chooses to light his cigarette with.

There’s also the myriad kinds of humour employed during this sequence. Swartzwelder has always oscillated between comedy fundamentals and bracing absurdity, the escalation of the cigarette-lighting gag is a perfect example of this. There are dashes of surrealism with the bet on the big opera tonight, referential humour that isn’t entirely built on the knowledge of the reference in the Carlin & Martin jokes. There’s an excellent straight man in Bill the accountant character, one whose every line furthers the madness of Krusty’s situation, some black humour in Krusty’s consumption of endangered condor eggs and even a dose of infomercial satire which would have been significantly more relevant in the mid-90s. We even get a celebrity cameo you can set your watch to.

If the onslaught had continued like this for the full twenty minutes this episode would have become exhausting. Even a show like Harvey Birdman has moments where they let up on the gas and those only run for twelve. Instead, in the next scene Swartzwelder opts to proceed in almost the exact opposite fashion from how he started, by daisy-chaining a single joke across multiple scenes. It’s an utter luxury that he still had no need to use Homer Simpson in this episode thus far, a character who in The Simpsons’ prime is basically a cheat code thanks to his versatility, universality and stupidity, but it’s Homer’s impressionability that Swartzwelder opts to mine.

The joke is simple. Krusty establishes his clown college and puts up a new billboard. Homer drives past billboard after billboard intending to buy whatever’s advertised but dismisses Krusty’s one because clown colleges aren’t edible. Nonetheless, the advert burrows into his mind and each successive bit proceeds with Homer seeing clowns everywhere, in his dreams, in his friends and family and in people burning to death. Eventually, he’s so hypnotised by the billboard that he announces to everyone that he’s going to clown college, and I don’t think any of us expected him to say that.

There’s a jazz-like quality to the way these two sequences operate as shot and chaser in assembling the vibe of the episode, how an extended passage of wild improvisations might be followed with something slower, quieter, and more melodic. Think of the way “Solo Dancer” lurches into “Duete Solo Dancers” on The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady or the ending coda to “Layla” if rock is your jam. Interestingly, it’s the less complex second half that’s left the more perceptible legacy. New Billboard Day, Homer’s clown-related hallucinations and his dinner table pronouncement have all been regularly mined for memes.

So the episode is funny, incredibly funny, a masterclass in yellow. However this isn’t Killing Em Softly, there needs to be some sort of story to this episode. Brilliantly, threaded throughout the chaos of the episode’s first three minutes is the entirety of the plot, all of which is introduced as part of a joke.

Krusty is bad with money (Joke 2)

Krusty is so bad with money that he’s in debt with the mob (Joke 18)

Krusty sets up a clown college. (Joke 35 & 38)

The rest of the first act settles into a more routine Simpsons episode, with Homer attending clown college and a series of sketches based on various aspects of clownery, including the return of Krusty’s loop-de-loop.

The second act is about Homer realizing that this job isn’t the glory of being a clown and getting severely injured by malfunctioning parachutes, car crashes, and small children. That is until people start mistaking him for Krusty, which he promptly starts to abuse so he can get free stuff.

The third act begins after Krusty mistakenly thinks the Generals were due and bets against the Harlem Globetrotters with the mob in full view. He escapes and the mob attempt to hunt him down but find Homer instead. He’s kidnapped and taken back to the mob hideout only for the real Krusty to show up. Wacky shenanigans ensue which conclude with the episode being book-ended by another loop-de-loop trick. And it turns out Krusty only owed the gangsters forty-eight dollars.

I’m not going to list the litany of excellent and iconic jokes that occur over the rest of the episode, I’ve done enough of that in this article and I should stop, stop, it’s already dead. What sets this episode apart from another farcical affair like “Saddlesore Galactica” is simply that none of the plot elements emerge independently of the narrative. The plot is absurd but the absurdity is laid out in the space of three minutes and, gradually over the course of the episode, all those elements return as beats in the story. We don’t feel cheated by the forty-eight dollar bet the way we do by the jockey elves because it’s merely a final flourish on a logical and natural plot development, rather than silly plot twist because there’s no interesting way to finish this story.

In my opinion, it’s past time “Homie the Clown” got its flowers as top ten Simpsons and, personally, top two Swartzwelder. I could have written another couple thousand words on the rest of this episode, if you’ve seen it you know what I’ve glossed over and I am sorry. Still, few single episodes of television have ever served as such a comprehensive exhibition of such ferocious a comedic talent and it’s as funny today as the day it aired.

I loved the flow-chart of the jokes. It totally helped to see the visual, plus I'd seen the episode recently. I reckon the Cartridge Family is another underrated Swartzwelder episode.